A few splintered images.

A dance floor in the Amnesia nightclub on Ibiza, an island off the coast of Spain. Girls with glitter on their faces. Sweaty skin and t-shirt as you squeeze your way from bar to podium. Smiles and high-fives. A crowd juiced up on house music and ecstasy.

In a basement room in Marylebone in London I sit slumped in a plastic chair, the kind you get in schools. Around me, a throng of men and women, some old, some young, some rich, some poor. All are straining forward to hear the speaker, a guy in his sixties, an actor, quite well-known, telling the story of how he nearly lost his liberty. sanity and life to the demon drink, and how it was only through hitting rock bottom and discovering a power greater than himself that he was able to turn things around.

On a battered old couch in a nightclub at the end of the world (actually Berlin) I smoke shisha and watch as a girl gets fucked until she squirts, and the man next to me carves out a fat line of cocaine to snort. He inhales with studied disinterest.

A trio of dissolute memories. There are many more. Like the time we all stood in Trafalgar Sq and watched the Pet Shop Boys perform a specially-composed electronic soundtrack to the film Battleship Potemkin. Seeing La Boheme at the Royal Opera House with my father and his girlfriend. Creamfields in Liverpool for the millennial. The massed crowds in the ruin bars in Budapest. A lecture by Martin Amis in London. Twilo in Manhattan. Christmas church services when I was at school. Seeing Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf at the Apollo with my mother.

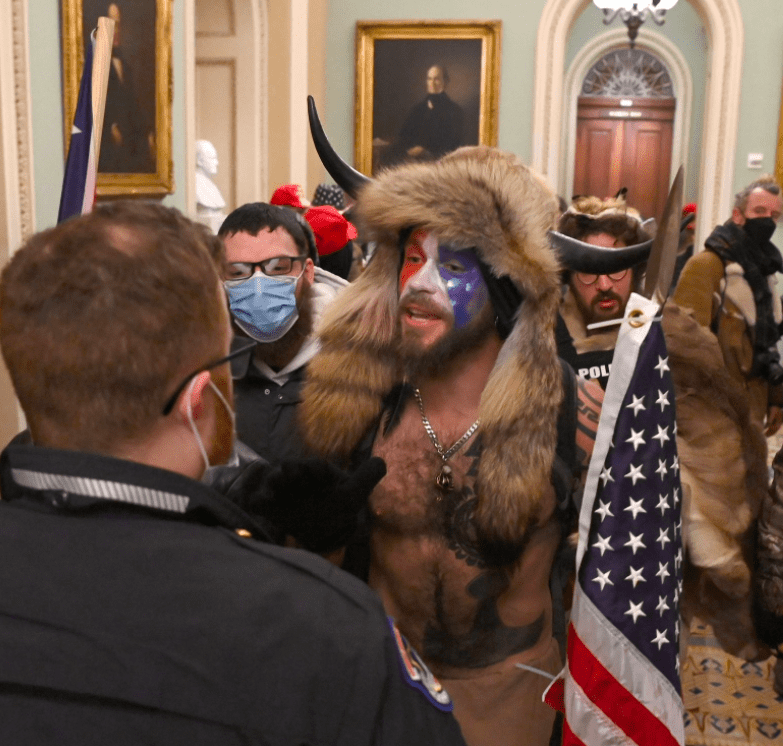

What do all of these things have in common? Quite simply, all of them are predicated on people coming together. On their converging, commingling, communing. On their singing together, dancing together, worshipping together, feeling together, emoting together – and sometimes emoting bodily fluids together.

The other thing these disparate activities have is that all of them have been banned across most of the Western world. Seriously – work your way down the list. How many of the things I’ve mentioned here could still take place?

That’s right – none of them.

And now, from where I’m sitting in East London, it looks like it will be a very long time before they are permitted again, if at all.

Togetherness – the coming together of people to love, laugh, experience, worship and protest, has died. We have killed it, and replaced it with the cold comfort of the Zoom screen.

One of the great tragedies of lockdowns is that they rob us of a very fundamental human experience – that of coming together with our fellow men and women en masse.

The line humans are social animals gets thrown around a lot, but I haven’t seen much research on why it is we have this deep drive to come together. Regardless, it is present and it is vital – for our mental, material and spiritual health.

In London, face-to-face alcohol recovery meetings are still running, although a great many former members now prefer to attend online instead. But the stalwarts who still brave the real world experience all say the same thing – Zoom is just not the same.

And of course that goes equally for yoga classes, school lessons, football matches and religious services as well. There is just something about getting a group of people into the same space that is powerful. An energy that is inimitable.

I have always been a misanthropic, narcissistic, introverted loner. I have spent a lot of my life thinking of myself as (a) better or (b) worse than the rest of the human race (and sometimes both at the same time). But even I crave that energy – the energy that is ignited by communion. That is created when a group of people – sometimes friends, often strangers – get together in a common pursuit or cause.

I crave it, I miss it and I mourn it. Because right now it’s hard to imagine it coming back. Or not for a long time, anyway.

When you are living through times of great turmoil and change it’s hard to interpret events as they happen, or even to collect them together into a single cohesive narrative. And certainly early last year it was difficult to comprehend the degree to which the fundamental underpinnings of our lives had been royally fucked. With time things became depressingly clear, and in this case hindsight was decidedly not a great thing.

And who knows where we’ll end up?

Optimistically we may see an easing of restrictions and some return to normality later this year. But I suspect the scars of what has happened will last much longer. And whenever we finally emerge, bloody, bruised and battered from this, we must remember what we lost, and what we must protect.

[…] Francis gives one account in his post, The Death of Togetherness (2021 January […]